- Published on

Keep it Simple, Stupid with React Components

- Authors

- Name

- Hoh Shen Yien

Table of Contents

Dealing with large React components has always been a hassle, if not a nightmare to me. Keeping track of all the useState, useEffect, useMemo... And boom, an infinite loop!

Background Story

In one of my past projects, I’ve come across an entire module of components with thousands of lines. As a result, no one dares to divide it, and every addition will be done right on top of existing codes, further expanding it.

As a result, anyone who wishes to make a change will have to pray hard that the changes they made have no side effects elsewhere in the component.

Oh, and not to mention, it took me more than half an hour to understand the parts I need to change and what to change.

What’s Wrong with Large Components?

Increased Complexity

While some argue that putting all the codes in a single place helps reduce complexity since you need to navigate lesser, I think it’s pretty much the opposite. For any newcomers to a project, some time might be needed in both cases, but after some time, short components will be remembered much more easily.

For example, imagine the levels of nesting in a large component, can you still keep track of which component reflects which DOM Element with a glance?

return (

<Flex> <!-- This is probably the top level -->

<Group> <!-- Which one is this? -->

<Group> <!-- How is this different from previous? -->

<Flex>

<Text>

</Text>

<IconChevronDown />

</Flex>

</Group>

</Group>

</Flex>

);

Not to mention there’s still conditional rendering or mapping like these, even with IDE’s bracket highlighting or indentation coloring, I don’t know about you, but I’ll always get lost in these codes wondering

return (

// imagine nesting it one or two levels deep

// with lines of codes instead of TrueComponent

{isTrue ? <TrueComponent /> : <FalseComponent />}

);

Or even Hooks (example from Open Tender)

// This is not even half of it

const dispatch = useDispatch()

const isLoading = loading === 'pending'

const isMerch = order_type === 'MERCH'

const errMsg = handleOrderError(error)

let orderTypeName = makeOrderTypeName(order_type, service_type)

const isUpcoming = isoToDate(requested_at) > new Date()

const displayedItems = cart ? cart.map((i) => makeDisplayItem(i)) : []

const { lookup = {} } = useSelector(selectCustomerFavorites)

const { auth } = useSelector(selectCustomer)

const check = { gift_cards, surcharges, discounts, taxes, totals, details }

const {

eating_utensils,

serving_utensils,

person_count,

notes,

notes_internal,

tax_exempt_id,

} = details || {}

Now the question is, given the codes like these, how much time does it take for you to make a simple change?

Before you can make a change, you first need to find out where to change, slowly inspecting element by element, console logging state by state…

If you enjoy doing that, well, but if you’re like me, you probably hate doing this too.

Oh, and don’t forget to find out all the places that have been affected by the codes. You might have just changed a single value, but that value might be used in 10 different places, and good luck finding those out.

So what does this mean? Long component smells, it’s hard to comprehend, hard to add a new feature, hard to test, and hard to detect bugs.

Code Duplication

We all know that React’s component is reusable. Now, if you’re trying to copy over a feature from one component to another, and the component is deeply nested, and intertwined with one another, what will you do?

Select the parts, copy, and paste.

Now you have the exact same copy of codes in two places, and sooner, three, four, five…

Imagine making a change in one of the copies, what’s next? Copying the change and applying it all over, one left out means bugs.

Component Re-rendering

This is a bit more technical, but let’s say your codes are as follow:

const AComponent = () => {

const [a, setA] = useState("");

const [b, setB] = useState("");

const [c, setC] = useState("");

const [d, setD] = useState("");

}

Then the component will re-render if any of the states (a,b,c,d) changes.

Instead, we could have divided the states to the children components rather than concentrating all in one big chunk of component.

Source: Stackoverflow

When is a component too long?

While there’s no official documentation or guidelines anywhere, I usually stick with a soft limit of 100 lines and a hard limit of 200 lines.

When my component exceeds 100 lines, I’ll start to look for parts to extract into a separate file, unless it’s special like SVG component or animation component.

If my component is more than 200 lines, I know something’s wrong, and some parts shouldn’t stay here.

Dealing with Large Components

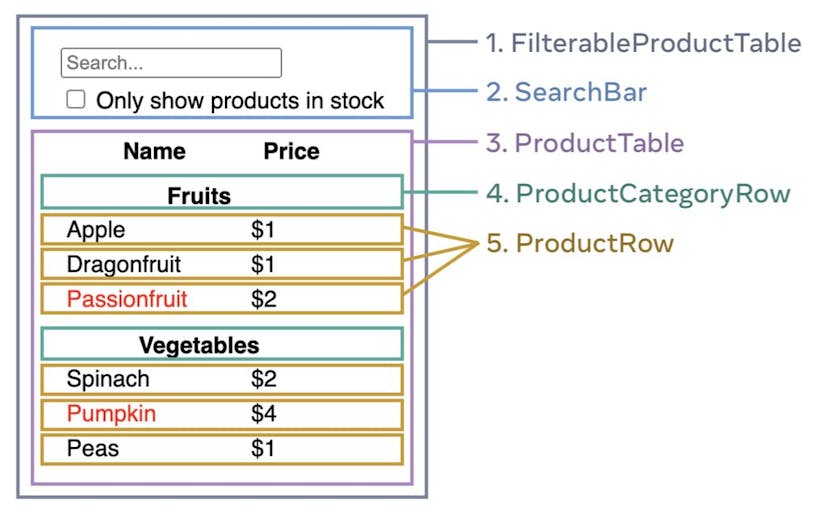

Breaking Down UI into Component Hierarchy

Usually, I have no issue breaking down large components, since there are always ways to break things down like in the image above.

If you really have no idea what component to divide, remember the good o’ Single Responsibility principle:

A component should do only one thing

If you think it has multiple purposes, break it down.

PS: React has written an amazing article on this matter, Thinking in React (I took the image there too)

Separating Hooks

Sometimes you might have defined many states and hooks to end up using one or two of them directly, while others indirectly:

const AComponent = () => {

const [a, setA] = useState("");

const [b, setB] = useState("");

const [c, setC] = useState("");

const [d, setD] = useState("");

const doSomething = (newString) => {

setA(newString.split(" "));

setB(newString + "test");

setC("prefix" + newString);

setD(newString == "test" ? "A" : "B");

};

const result = a + b + c + d;

return <p>{result}</p>

}

While it is a dummy example, it does happen often. In this case, except for the component being small itself, I will usually move the hooks into a separate hook function file:

// useSomeHook.js

const useSomeHook = () => {

const [a, setA] = useState("");

const [b, setB] = useState("");

const [c, setC] = useState("");

const [d, setD] = useState("");

const doSomething = (newString) => {

setA(newString.split(" "));

setB(newString + "test");

setC("prefix" + newString);

setD(newString == "test" ? "A" : "B");

};

return {doSomething, result: a + b + c + d}

}

Much cleaner, separating the logics into another file.

Separating Styles

Lastly, with libraries like Styled Components or even the use of inline styles, if you think your style is occupying too much space, it’s quite wise to move them out into another file too like this:

// Styled Component

export const Button = styled.a`

display: inline-block;

border-radius: 3px;

padding: 0.5rem 0;

margin: 0.5rem 1rem;

width: 11rem;

background: transparent;

color: white;

border: 2px solid white;

`

// Inline Style

export const whiteButtonStyle = {

borderRadius: "3px",

color: "white",

display: "inline-block"

}

// Or even Tailwind

export const whiteButtonClasses = "bg-white rounded-sm inline-block"

Directory Structure

After refactoring these, a component might end up like this:

- aComponent

|-- __tests__

|-- index.js

|-- hooks.js

|-- styles.js / styles.css

Conclusion

It’s a nightmare to deal with giant components, and it’s been mentioned in classics like Refactoring that lengthy codes are prone to bugs.

While it may take a few more minutes to break a component down, the future you will definitely appreciate it!

Save a few minutes now for hours in weeks later.